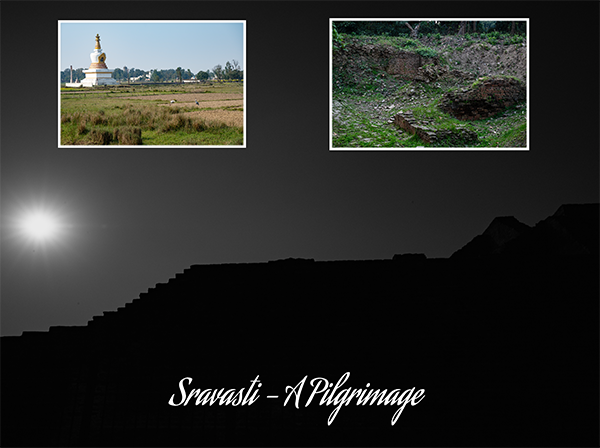

(Sanskrit – Śrāvastī; Pali – Sāvatthī)

To my parents.

The curiosity to know about the genesis of Sravasti played on my mind from childhood. I had to explain the spelling and meaning of my name to most people. If I did not have to explain, then it had to be a Bengali who, on hearing it, would break into reciting lines from two well-known Bengali poems – Nagarlakshmi by Rabindranath Tagore and Banalata Sen by Jibanananda Das.

The first poem refers to a famine in Sravasti during Buddha’s time. At Buddha’s call, a destitute woman came forward to help the poor by giving away her alms while the richest of men refused. The second is an era-defining romantic poem where the poet compares his beloved’s hair to the dark night of the city of Vidisha and her face having the superior craftsmanship prevalent in ancient Sravasti.

I felt an innate romanticism about this city on which the only information I initially had was that it existed in ancient India, somewhere in present-day Uttar Pradesh. I was excited to see Sravasti on the map in my school history book. It was situated near the old kingdom of Kosala. However, it was only in the 1990s when I learnt that the city of Sravasti still existed, from a magazine article detailing the excavation of an archeological site in the district of Sravasti. Subsequently, this place topped my bucket list but remained a distant dream for years. After decades, I managed to visit this uncut diamond in the crown of Buddhist pilgrimages, in February 2023. This was possible only due to its proximity to Nepal and my introduction to Swosti Rajbhandari Kayastha*, who gave me invaluable inputs on Sravasti before my journey began.

A map of 8 Buddhist Pilgrim sites near the India-Nepal border

I crossed over the Nepal border from Nepalgunj and traveled for 2 hours on the NH 927 and 730 through Bahraich, to reach Sravasti that lies at the foothills of the Himalayas, near the West Rapti River. The nearest Indian towns are Gonda, Balrampur and Lucknow. I was booked in a standard hotel called The Sravasti Residency, on the highway, next to Platinum Sravasti and Lotus Nikko hotels. The Residency is comparatively new, clean and with good service. Having come in search of history, I managed to contact a septuagenarian guide, Anantram, to take me around this sleepy agricultural town where most pilgrims spend just a day to visit only 2-3 Buddhist sites. Anantram worked for 10 years with the archeological team, which excavated the site from 1986-87. The hotel staff and guides were astonished that I wanted to stay for 2 days. My interest lay in Sravasti’s history of the Buddha and beyond. I, categorically, did not want to visit the newer viharas built by the Burmese, Chinese, Sri Lankans and Thais.

Sravasti Ghosh Dastidar in front of The Sravasti Residency, in the Sravasti district

Sravasti is one of the 8 most important places in the Buddhist pilgrimage circuit that are thronged by Japanese, Korean, Chinese, Thai, Myanmarese, Vietnamese, and Sri Lankan pilgrims. Sravasti is where Gautama Buddha spent 24 varshas/vassas (monsoons) after his enlightenment, imparted many of his suttas (sermons), converted most of his famous disciples and performed the Twin Miracle.

Although Sravasti is known for its association with the Buddha, its history dates to the Puranas and is mentioned in the literature of all major Indian religions. In Pali, it means a place where everything is complete and in Tibetan it means a place that has everything. As the prosperous capital of Kosala, an important kingdom among the 16 Mahajanapadas, Sravasti was a political, economic, religious and philosophers’ hub during the 5th & 6th century B.C.E. The other cities of Kosala were inferior in status and affluence when compared to Sravasti. The north to south-west trade route went from Sravasti to Pratisthana with stops at Ujjain, Vidisha, Kosambi and Saket. It is extensively cited in the epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata, Harshcharita and Kathasaritsagar. According to the Ramayana, Lord Rama divided Kosala into two parts, gave Sravasti to Luv and Kushavati to Kush. In the Mahabharata and Bhagavata Purana, it is said to have been built by a Suryavanshi king named Sravasta, the son of King Srava and a descendant of Vaivasvata Manu. King Sravasta might have named it after the Sage Savattha.

In the Ajivika and Jain literatures, it has been referred to as Saravana, Kunalnagari and Chandrikapuri. It is sometimes called Saheth-Maheth (Sahet-Mahet) in archeological research papers. In 1862-63, A. Cunningham discovered the mounds of Sahet and Mahet. He identified Mahet as the actual ancient mud-walled city of Sravasti that was totally damaged when excavated. Ruins of residential homes, stupas and shrines made of bricks were unearthed here. One of them yielded numerous terracotta panels depicting scenes from the Ramayana in the Gupta style. There are also some medieval Islamic tombs on the northwest of Mahet. It has some very old and important Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist ruins. Bordering Mahet is the smaller site of Sahet, which Cunningham recognized as Jetavana.

I thought I would start my touring from the very beginning.

Sitadwar – Treta Yug

Anantram took me to Sitadwar (in Tenduwa Mahant, Bahraich) where ancient idols of Sita and Lakshman had been unearthed. The locals believe that this was where Valmiki’s ashram was located and Sita spent her exile. Lakshman left Sita nearby and when she was thirsty, he made a hole in the ground with his arrow that transformed into a 900-acres jheel (lake), the biggest in the area. Luv and Kush were, apparently, born and raised in this forest of which just a handful of trees exist; and captured Ram’s horse of Ashwamedh Yagna. The simple Sitadwar temple and the Valmiki temple behind it are regularly visited by devotees during Akshay Navami, Devotthani Ekadasi and Kartick Purnima. A big fair is held annually during these 3 days. The Sitadwar lake is scenic with aquatic vegetation and migratory birds. I could not determine the authenticity of the Treta Yug reference as the Internet throws up 2 more places in India, where Valmiki’s ashram might have been. However, the temples related to the Dwapar Yug seem to have more validity, though both are based on legends.

Sita And Valmiki temples, beside the jheel at Sitadwar, Tenduwa Mahant Bahraich

Prithvinath & Pacharannath temples – Dwapar Yug

The Prithvinath and Pacharannath temples in Khargupur, Gonda are placed at stone’s throw distance from each other, in the Sravasti District. Legends say that during their Agyatvas (in disguise), the five Pandavas established four Shivalingams in this area of Chakranagari – Loknath by Yudhisthir, Prithvinath by Bhim, Pacharannath by Arjun, and Amritnath by Nakul and Sahadev. The region was subsequently named Belchakra and Jhali Dham.

Research by the Government of India’s National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities states that the Prithvinath temple might have been built by the Gahadavala kings (11th -12th century C.E.) and renovated in 1282 C.E. by Ram Chandra Paramhans Giri. The research associates the mythological reference to the temple. Covering an area of 100 m x 50 m, the temple is made of bricks, stone, and lime, and has a sanctum sanctorum with a pradakshinapath (circumambulatory). The lingam and a copper plate grant were excavated from under a 20 feet high mound. The lingam goes 44 feet below ground and is, supposedly, the world’s tallest. Only a few eroded sculptures and red ware have survived the years.

While the Prithvinath Temple is well-looked after and frequented by believers, the Pacharannath temple seems like a neglected brother. The temple’s structure is almost the same but has not been painted in ages, with plants growing roots and parrots finding a resting place on the shikhara (tower). The priests’ families have served the temples for generations. However, they did not have much information about the temples. Anantram, being a digger during the excavations of 1986-96/97, knew more about Sahet-Mahet, Orajhar and Purvaram Vihar.

Prithvinath Temple and the huge Shivalingam on top. Pacharannath and the smaller lingam at the bottom

Archeological Excavations

Archeological expeditions in this region were led by Cunningham (1862) and thereafter by Dr Hoe (1874-1876 and 1884-1885), Vogel (1907-08), Dr K.K. Sinha (1959) and Archeological Survey of India in association with the Archaeological Research Institute of Kansai University, Osaka, (Japan) from 1986 for 10 years.

As mentioned above, Cunningham found Sahet-Mahet (measuring 286.026 acres). He unearthed several temples and monasteries, including the Mulagandha Kuti in Jetavana and inscriptions of Gahadavala kings Madanpal and Govind Chandra that confirm donations by these kings to the Jetavana Viharas. Excavations led by Dr Sinha exposed terracotta figurines of the Mother Goddess, a Naga and several Mithuna idols, along with jewellery, and short sections in Brahmi script.

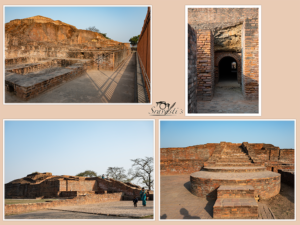

Japanese archeologists dug deeper layers and unearthed relics from the 8th century B.C.E. It was evident that Sravasti was damaged by annual floods and citizens tried rebuilding the monuments repeatedly. A thick layer of untouched charcoal and combustion residue across many sites of the Buddhist chaitya complexes, indicated that the stupas burnt down at the same time and were deserted by the monks. Excavations at Mahet revealed well-planned housing complexes, temples, stupas, citadel and the eastern gate with 3 security points with watchmen’s platforms. A mud rampart with around 30 openings was discovered at Mahet from where the old bed of river Rapti (ancient Achiravati) could be seen on the north-eastern side. The archeological teams also discovered an ancient earth road leading to the city. The houses had proper sanitation and drainage facilities with soak pits; the rooms were placed around central courtyards where water would be stored in big pitchers; wells and ring wells for storing water and grains. Also found among the ruins were numerous terracotta human figurines, toys and punch-marked silver and copper coins, Ayodhya and Kushan coins. Anantram described how reconstruction and conservation were done brick by brick and layer by layer at the same trenches from where the bricks were dug out.

Some significant findings on the western part of Mahet were the remains of Jain art and architecture belonging to the 4 century B.C.E. to 12th century C.E. After that, these were most probably destroyed when Alauddin Khilji raided Sravasti.

Mahet – The Jain Era

Contrary to Sravasti’s violent destruction, serenity prevails in all its Jain and Buddhist sites today. I had found Lumbini very crowded, noisy, and curated. Kapilavastu was more to my liking as it had only the restored ruins with very few sightseers. Sravasti reminded me of Kapilavastu and Nalanda. The brick ruins have been well-preserved and selfishly, I was grateful that not many tourists visit these places.

As I entered the sprawling rectangular courtyard of the ancient Jain temple of Bhagwan Sambhavnath or Shobhnath, there was not a single soul around. I took a little time to soak in the tranquility and architecture. As I looked at the converging flight of steps leading to the 10 ft x 10 ft shrine, I had to appreciate the precision of the structural design. On reaching the top-most platform, I got a picturesque view of smaller ruins among an agricultural landscape. The temple has distinctive architectural features that are not in any other structure in this region – it has two courtyards at different levels and instead of a spire, has an Iranian style lakhauri brick vault, of which only half remains. The inner wall of the sanctum has several niches where the Jain idols must have been kept. Many idols related to Jainism, including idols of all 24 Tirthankaras, were found here. An almost 1000-year-old seated idol of Bhagwan Rishabhdeo, engraved on a flat stone, was discovered here with magnificent carvings of an ox, lions and yakshas.

This is a sacred Jain pilgrimage as it is the birthplace of the revered 3rd and 8th Jain Tirthankaras Bhagwan Sambhavnath and Chandraprabha. An annual fair is held on Kartick Purnima where Jain devotees donate vast amounts of money and bring raths (chariots) and elephants.

According to the Ajivika literatures, Guru Gosal Mankhaliputra, was born in Sravasti.

Jain temple of Bhagwan Sambhavnath or Shobhnath with its dome, niches and sprawling courtyard. Ruins outside the temple complex

Mahet – Buddhist Period

A few kilometres away from the Jain temple, lie the impressive monuments of the Sudatta Stupa or Kachchi Kuthi and the Angulimala Stupa or Pakki Kuthi. The excavations during 1907-11 revealed ruins of brick stupas and shrines, residences, three hundred terracotta panels, illustrating scenes from the Ramayana in the Gupta style.

Fa Hien, the Chinese Buddhist Monk, visited Sravasti in the 5th Century C.E., during the reign of Chandragupta II. He observed that important Buddhist cities like Bodh Gaya, Kapilavastu, Sravasti and Kushinagar were not cities anymore. Only 200 families inhabited Sravasti, and the roads were safe to travel. Fa Hien was looking for a written version of the Vinaya Pitaka and in Sravasti, he “obtained a copy according to the text accepted at the First Great Assembly and practiced by priests generally while the Buddha was still alive”. Fa Hien did not mention the ruins of the King Prasenjit’s palace or the chapel, which he built for the Buddha. However, this reference was found in Hiuen Tsang’s memoirs.

Hiuen Tsang travelled about 100 miles north-east from the Visoka district and reached Sravasti (Shih-lo-fa-si-ti). The city was in wild ruins but with some honest inhabitants who were interested in learning and working. The mild climate was suitable for good crops. There were hundreds of dilapidated Buddhist monasteries with a few inhabitant Sammatiyas and many Hindu temples. Since Sravasti was King Prasenjit’s capital, Hiuen Tsang located the foundations of the old ‘Palace city’. On the eastern side, he found ruins of the large chapel that the king had built for Gautama Buddha. He also came across the ruins of the nunnery of the Buddha’s foster mother, Bhikkhuni Prajapati. On the east of the nunnery lay the site of the house of Sudatta (Anathapindika) and a stupa where Angulimala (Finger garland) gave up his evil ways to become the Buddha’s devout disciple and subsequently, an arhat (saint).

The Angulimala Stupa/Pakki Kuthi is a terraced monument on a rectangular platform that is currently under maintenance. It has signs of structural additions and modifications of different periods, maybe starting from the Kushan Age. Fa Hien determined that this was where Angulimala was cremated. A tunnel through the mound, drainage for floodwater and constructional supports were made during excavation to preserve the memorial. Buddhists regard Angulimala as a symbol of spiritual transformation, from violent brigand to an embodiment of peace.

Before excavation in the 1980s, there was a mound and a tree at the Sudatta Stupa/Kachchi Kuthi or the house of Sudatta. A pious Buddhist setthi (merchant) with immense wealth, Sudatta was popularly addressed as Anathapindika – one who gives alms to the unprotected. A gradual flight of terracotta steps leads to a platform from where the sunken substructures of two circular stupas are seen. The stupa has an impressive structure that has remains of several alterations done during the 1st to 12th centuries C.E. Fa Hien noted that the stupa was erected on the foundation of Sudatta’s house. However, the numerous relics and other structural ruins excavated here, reveal that there might have been a Brahmanical temple from the Gupta period below a Buddhist tope from the Kushan period. An inscription on the lower portion of a Bodhisattva image, unearthed at this site, tells us that the Kachhi Kuti belonged to the Kushan age.

The majestic Angulimala Stupa with the tunnel made for preservation. The Sudatta Stupa with its converging steps

Sahet – Buddhist Period

Outside the south gate of Sravasti/Mahet, is Sahet. Fa Hien identified this as the Jetavana Vihara. There were two 70 feet high stone pillars – one on each side of the east gate, that were reportedly built by Emperor Ashok when he visited in 249 B.C.E. The pillar on the right had an ox on the top and the left one had a sculptured wheel. He stated that there were almost hundred Buddhist monasteries in a ruinous state. The only structure that withstood the ravages of time was the brick building containing a 5 feet high image of the Buddha created for King Prasenjit. Hiuen Tsang mentioned only the Jetavana monastery by name.

The structural ruins in Jetavana go back to the 1st and 2nd century C.E. Among them, the earliest unearthed artefact possibly from the Mauryan era, was a sandstone casket with bone relics, a gold leaf and a silver punched coin. The Buddha and his followers resided and meditated where only the foundations of old temples and stupas survived.

Jetavana is of supreme religious importance. Gautama Buddha spent 18-19 monsoons here and 6 monsoons at the Purvarama Vihara. He might not have lived in Sravasti at a stretch. Probably, he travelled to other parts of the country during the year and Sravasti was his monsoon retreat. Even now, monks go into retreat during the monsoons as it is difficult to travel around in the rains. Scholars believe that 871 suttas in the four Nikayas (collection) of Buddhist canons, are based in Sravasti.

After meeting the Buddha and listening to him preach in Rajagriha, Anathapindika became the former’s chief male patron. He invited the Enlightened One to Sravasti. Since Gautama Buddha was an ascetic, he would not stay in any palace or household. Anathapindika identified a peaceful and secluded garden named Jetavana (garden of Jeta – the son of the king) that belonged to Prince Jeta, son of King Prasenjit of Kosala. Anathapindika offered to buy it to build a huge monastery for the Buddha. Jeta told Anathapindika that he would sell if the latter covered the entire area with gold coins. The coins that Anathapindika brought covered the grove except a portion near the entrance. He ordered for more coins. However, inspired by Anathapindika’s faithful determination, the prince donated the remaining land, gave valuable timber, and erected a wall around the grove with a humongous gateway. Ananthapindika built the spacious monastery with rooms for the monks, nuns, and travellers; storerooms, halls with fireplaces for exercise and various services; walkways, wells, bathrooms and ponds. The Jetavan Anāthapindikassa ārāma (Pali, – in Jeta Grove, Anathapindika’s Monastery) came into being. The name of the monastery was in accordance with the Buddha’s wishes to commemorate both the benefactors’ faithfulness and generosity.

Gandhakuti, Kosambikuti & other stupas with the Anand Bodhi tree at Jetavan

I visited Jetavana in the late afternoon. The golden hue of the setting sun washed over the quaint historical park with lush foliage bordering the walls and the cloisters. There were monks in kasayas and some international pilgrims, mostly wearing white, offering homage with incense sticks and flowers at the bases of the different brick temples. The monuments are well-marked with relevant information. Even if you are not religious, you will feel like immersing in the serenity of this holy place, sit quietly, and imagine how splendid Gautama Buddha’s residence with his bed, the Gandhakuti (Perfumed Chamber – Temple no. 2), must have been. It used to be a 7-storeyed sandalwood building, built by Anathapindika, that was destroyed by a fire, later on. Fa Hien and Hiuen Tsang saw a dilapidated two-storeyed brick structure. Shining during sundown, a small replica stands near the entrance to the main stone platform surrounded by low walls. Some pilgrims have covered this with gold foil. Adjacent to this, is the Kosambikuti (Kosambi, an ancient city; Temple no. 3), the Buddha’s meditation room. Facing the Gandhakuti, is Stupa H where he delivered his sermons to his disciples. Adjoining this, are a well where he bathed and two elevated rectangular brick terraces marking the original chankama (promenade) where he went for walks.

Soaring high above the stupas, is the now fenced and propped up, ancient Anand Bodhi tree. Anathapindika wanted an object to offer prayers to during the Buddha’s periods of absence from Jetavana. He planted a sapling from the original Bodhi tree in Bodh Gaya, here. The great disciple Anand asked the Buddha to meditate under the tree to reinforce its blessings. The tree was named after Anand who supervised its planting and sanctification. Now, monks meditate under its shade and hand out dry leaves of this sacred tree to visitors. Neither the Internet nor my guide could ascertain if the tree is from the original shoot or its descendent.

There are stupas devoted to his great disciples. Some of the structures have ambulatory passages around a central chamber, signifying that these must have contained images. The largest structure is Temple and Monastery #19. It has a shrine, a well within the courtyard, a portico and 21 cells for the monks’ use. It might have been rebuilt 3 times during the 6th and 11th-12th centuries C.E. Among the most significant findings in this site were an engraved copper plate charter of Govindachandra of Kanauj (1130 C.E.) that granted certain villages around Sravasti to the Jetavana Mahavihar monks; a Gupta-age clay tablet portraying the Buddha seated in the Dharmachakra Mudra; a Buddha image in Bhumisparsha Mudra and a sculpture showing him receiving a bowl from a monkey, both belonging to the 10th century C.E. Near the eastern wall is an octagonal well. The other wells are all circular in shape. Outside the Jetavana premises and overlooking its picturesque bathing tank is a monumental golden statue of Lord Buddha and the famous Daen Mahamongkol Chai Temple, built by Maha Upasika Sitthipol Bongkot of Thailand in the 1990s.

Golden statue of Lord Buddha & the Daen Mahamongkol Chai Temple overlooking a bathing tank at Jetavan

Next day, I revisited Jetavana at dawn, hoping it would be emptier. Contrarily, it was full of Vietnamese, Japanese, and Sri Lankan pilgrims. The Sri Lankans were preparing to perambulate the temples in a procession, with colourful umbrellas and flags, reminding me of the peraheras (processions) we watched during our stay in Colombo. Despite the number of devotees, the place was incredibly tranquil with soft, solemn chanting and scent of incense sticks permeating the crisp wintry air.

Pilgrims praying at Gandhakuti. Sri Lankan pilgrims preparing for a procession in front of Gandhakuti, Jetavan

Orajhar Mound – Buddhist Era

Apart from the above and the numerous smaller mounds, the Sravasti district has two more sites of utmost importance. On the highway, near the Sravasti Residency, lies the Orajhar mound. Unlike Sahet-Mahet, the Archeological Survey of India has not posted any board with the details of the site. Only a board marking it as a heritage site stands at the entrance. After hiking up a worn-out trail to the top, I was welcomed with a stunning 360 degree view of the green agrarian fields with cows, buffaloes and migratory birds. I went around the star-shaped monastic complex from the Kushan period. A handful of pilgrims meditated in the middle of a base that used to be a temple from the Gupta period. Archaeologists have dug out the remnants of a brick stupa that might have been built by Emperor Ashoka.

The main attraction of this venerated site is that the Buddha performed the Yamaka patihariya (Twin Miracle) and other miracles here, under a mango tree planted by the gardener Ganda. To silence his pedantic dissenters, he created a jewelled walk in the air and stood on it. The Buddha levitated on a thousand petalled lotus and appeared in pairs of opposite characters, like producing fire from the upper part of his body and streams of water from bottom part, and vice-versa; also, alternating the same from on his right and left sides. Six colours emanated from every pore of his body towards the heaven and the netherworld. This Miracle lasted for a long time and was followed by other miracles that went on for sixteen days. During the entire span, the Buddha gave sermons answering various philosophical questions. Then, he proceeded to heaven to preach the Abhidhamma Pitaka to his departed mother. The illustrations and sculptures depicting this Miracle find place in many Asian Buddhist art and architecture, like the Sarnath Stupa, Ajanta and Kanheri Caves, and in Gandhara Arts.

Orajhar Mound where the Buddha performed the Twin Miracle

There are two more mounds nearby at Penahiajhar, and Kharahuwanjhar where many Buddhist relics have been discovered. However, I did not visit these mounds. Instead I visited the revered Purvarama Mahavihara or Pubbarama Monastery, donated by the Buddha’s chief benefactress, Mrigara Mata Visakha.

Purvaram or Pubbarama Mahavihara – Buddhist Period

The site of the Purvarama (Eastern) Monastery is a few metres away from the Orajhar Mound. A narrow rustic road winds into a peaceful semi-forest area to reveal a raised ground with the stump of an Ashokan Pillar. Two rusted boards with almost illegible writing declares it to be the Monastery erected by Mrigara Mata Vishakha. Alongside the pillar, is a semi-dark modern room, with a few broken relics of red stone, a Buddha idol donated by the Thais and a cupboard of religious texts. Regular thefts have depleted the monastery of many more artefacts.

Vishakha was an aristocratic lady who supported the Buddha and his followers during a major part of his ascetic life. She converted her father-in-law Mrigara into a devout Buddhist, after which, she was known as Mrigara Mata. She donated 9 crores worth gold coins and a piece of land to the Buddhist Sangha. The Buddha accepted this donation and requested her to build a vihara. The monastery was two-storeyed with meditation halls and 500 residential rooms for monks and nuns on each floor. Of the 24 monsoons that the Buddha spent in Sravasti, 6 were spent here where he preached 23 important discourses. Some believe that the ashes of Vishakha were interred here.

Fa Hien mentions that this site was to the north-east of Jetavana. King Ashoka visited Sravasti in 232 B.C.E. and erected 2 pillars. The pillar used to be around 80 feet long and thicker at the base. The Archeological Survey of India excavated only 7 feet. It was damaged during the Hun and Muslim invasions in 512 C.E. and between the 9th and 12th century C.E., respectively. It is now being worshipped as a Shivling! Further excavations may reveal the original room donated by Vishakha. Idols of Vishnu and Hanuman and quite a few red stone containers have been found here.

Purvarama Vihara, the Ashoka Pillar, some red stone relics and a rusted signboard

Currently, hardly anyone visits this place. The simplicity and peacefulness of these religious sites steeped in history, left me with a dichotomous question. Should this lesser known jewel be advertised to attract tourists and commercialism? Or, should it be left in peace that is so perfect for Buddhism? Personally, the balance tilts heavily towards the latter. However, I would not mind if the Archeological Survey of India excavated further and set up a protected centre with more information about the sites.

My quest for knowledge about the genesis of my name was answered to a great extent but I have a thirsty soul. I may return again, without my laptop and camera.

Indebted to:

- *Swosti Rajbhandari Kayastha – Lecturer of Museum Studies and Nepali Art History, Lumbini Buddhist University, and Curator at Nepal Art Council

- Dr Kakoli Sinha Ray – Associate Professor of History, Lady Brabourne College, Kolkata

- Map of Sravasti by Swati Mitra – Bengali Teacher, South Point High School, Kolkata

- Anantram, my guide

Sources:

- Hwui Li, Shaman – The Life of Hiuen-Tsiang

- Watters M.R.A.S., Thomas – Yuan Chwaig’s Travels in India 629—645 A. D.

- Sankrityayana, Rahula – From Volga to Ganga

- Chakrabarti, Dilip K. – Archaeological Geography of the Ganga Plain: The Lower and the Middle Ganga

- The Internet