On World Alzheimer’s Day

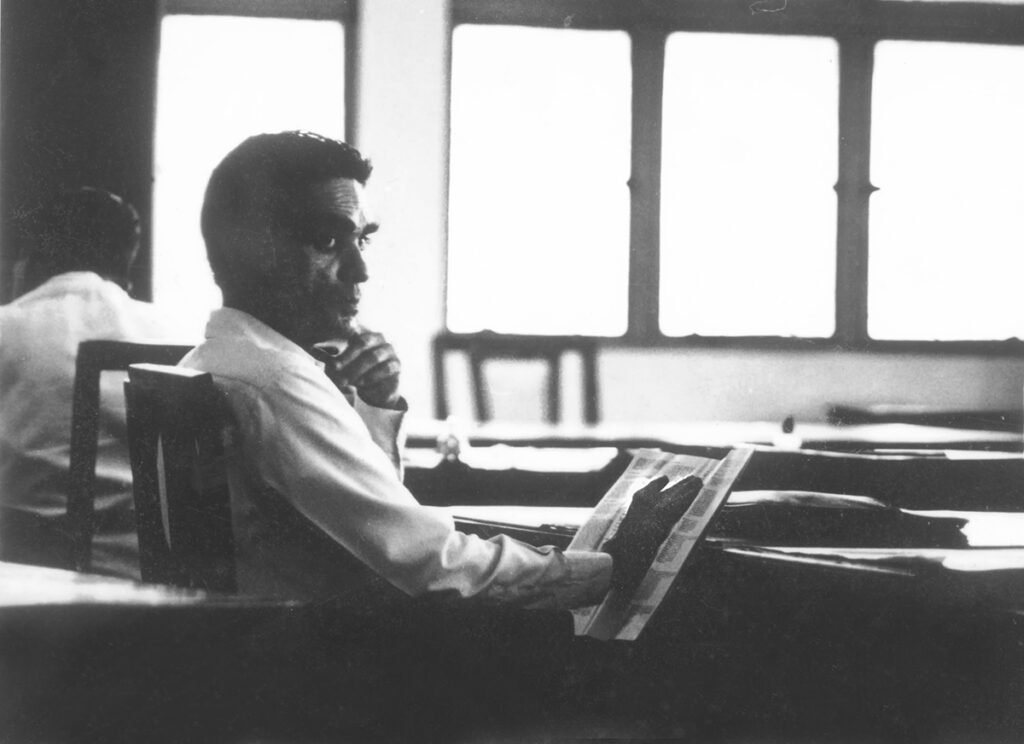

The three things that I most remember about my father, (Baba as I called him), was his mastery over both English and Bengali; the ease with which he did the cryptic crosswords in The Statesman in minutes. Also, his vast knowledge of numerous subjects and the immense capacity to remember dates and events accurately. He was our Thesaurus, encyclopaedia and our very own google and wiki put together, till the time he started forgetting even the simplest of things.

In total contrast to his photographic memory was his forgetful nature. He would forget where he had put his cup of tea, or the names of people he met regularly, or to wear pants and left the house with the towel still wrapped around his waist. We were all aware of this, and so did not detect the early signs. The alarm bells rang when he asked my sister six times, in a span of fifteen minutes, if she had offered me tea.

MRI and tests confirmed our worst fear – he had Alzheimer’s disease. It was easier to explain the disease to my father, than to reconcile to the fact, that the person who could remember almost everything he ever read or heard, had a disease that would make him forget everything eventually. Our priority was to maintain normality around him while dealing with dementia. For the first, two and half years, Baba tried to lead a normal life and we encouraged it as much as possible. But, he forgot his way back home a few times from the bazaar, which was ten minutes away and we went frantic searching for him while hoping he didn’t meet with any accident. As the disease started taking a firmer grip on him, we had to restrict his movements. Being confined at home took a toll on his health and his quality of life was compromised.

My mother, the primary care giver, was in denial for the entire duration of three and half years, that my dad struggled with the disease. She would constantly tell him to make more effort to remember recent events and stop repeating things. She genuinely believed this exercise, would keep his brain busy and slow the progress of the disease. She, gradually become obsessed with this and believed she could make him well. This was painful not only for Baba but mostly for her, because deep inside she knew how futile this was.

Baba was well loved. Most people, although perplexed by the disease, were sympathetic. Initially, they tried to cope with it by ignoring it. They attributed his dementia to his usual forgetfulness, which had increased with age. He would often become depressed because he could feel something was amiss. His short-term memory loss, hampered his ability of coherent speech. People found it more and more difficult to talk to him, as the dementia progressed. His relationship with some people changed because they didn’t know how to behave around him. They didn’t know how to deal with someone, whose reality was not the present but forty years in the past. Few people even made fun of his confused speech. Some lamented his memory loss on his face. Some shook their heads and looked at him with pity.

No one deserves pity. People suffering from Alzheimer’s least of all. They merit our respect and understanding of the difficulties dementia causes and the wisdom to work around it. I think we needed a more holistic approach to Baba’s changing needs. We needed to accept, that he’ll not be the person we knew, but will always be the person we loved.